Hello! As a disclaimer, I would like to announce that this article is a reprint (so to speak) with light edits for legibility, of my exam paper in my 18th Century Art course I took last year. I really liked this class, and I recently found this paper hidden away in my files, and I wanted to share it with you guys. I already passed this exam, so I can’t be flagged for plagiarism… right? It’s also way too long for email formatting, please read it on the Substack website or app!

Enjoy!

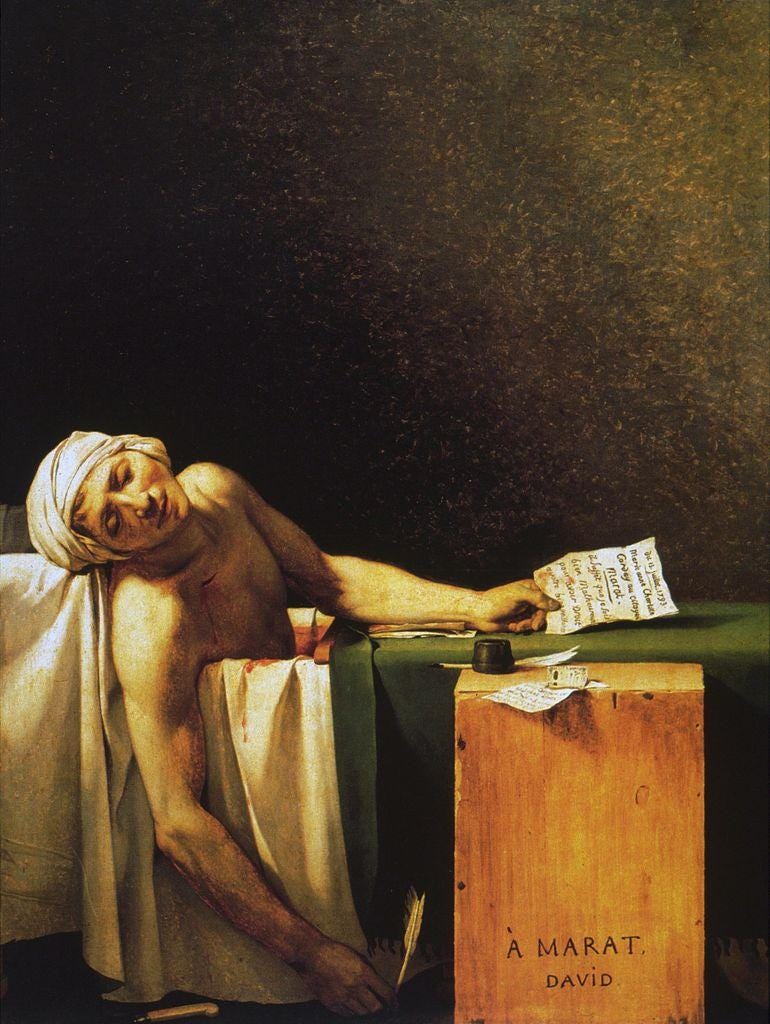

This paper will take a brief look at the earlier works of the French artists Élisabeth Vigée-LeBrun (1755 – 1842) and Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825), before using the paintings “Marie Antoinette and her children” (figure 2) and “Death of Marat” (figure 4) to discuss how the artists were influenced by the political and social environment of their time, and how this political unrest came to be the driving force behind their changing the status quo of their respective genres.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun was a French woman portrait artist during the late 18th century and early 19th century, who, together with other women painters such as Angelica Kauffman and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, worked on commissioned portraits for queens such as Charlotte of England, Maria Carolina of Naples, and Marie Antoinette of France.1 Vigée-LeBrun studied with her portraitist father Louis Vigée during her childhood, and married the art dealer Jean-Baptiste-Pierre LeBrun in 1776, whose ancestor was First Painter to King Louis XIV and one of the founders of the Académie Royale.

It was these connections to the monarchs that secured her work, and later a place at the Académie Royale by order of the King.2 She achieved great success in France, and later European cities such as Florence, Naples, and Vienna, during one of the most politically turbulent periods of European history.3 Due to her close association with the monarchs, it was dangerous for her to live in France during the revolutionary years. She lived in exile in Italy and Russia, where Queen Catherine the Great offered her refuge, until 1805.4

Vigée-LeBrun first painted for Marie Antoinette in 1778 (although the artist herself writes in her Memoirs it was in 17795): a highly formal full-length portrait of the Queen dressed in a hooped skirt and tall, powdered hairdo, intended for her Habsburg family in Vienna (figure 1).6 The painting was a commission from the Queen herself, as her mother, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, was requesting a portrait of her daughter.7

The artwork is painted in a soft manner, with invisible brushstrokes; the fabric of Marie Antoinette’s dress is smooth like silk and reflects the light, which comes in from the left side in a soft yet determined manner, illuminating Marie Antoinette, the flowers, and parts of the background. The Queen is surrounded by expensive-looking furniture; on her left stands a table draped in red cloth on top of which stands a vase of pink and white flowers, and a cushion with the royal crown on it. In the right top corner, we can see a bust sculpture of King Louis XVI adorned with the figure of Justice8, a visual reminder to the viewer of the royal marriage, standing out against the dark green curtain, which the light does not fully reach.

Perhaps one of Vigée-LeBrun’s most famous paintings depicting Marie Antoinette, and which will be the primary painting of Vigée-LeBrun’s that this paper will look at, is the 1787 Portrait of Marie Antoinette and her Children (figure 2). This is the last painting Vigée-LeBrun did for the Queen9. In this painting, we see the Queen with her three children, one on her lap and two standing next to her, sitting by an empty crib. She might be sitting in the Salon de la Paix, a junction room between the Hall of Mirrors and the Queen’s Great Apartments, the former of which the vault was painted by Charles LeBrun, the ancestor of Vigée-LeBrun’s husband, in 1678.10

The boy on the viewer’s right – Marie Antoinette’s eldest son Louis Joseph, nicknamed Le Dauphin, and heir to the throne – is pointing towards the empty crib, reminding the viewer of Marie Antoinette’s second daughter Marie Sophie Hélène Béatrix, who had passed away at only eleven months old earlier that year. Upon her lap sits young Louis Charles, Duke of Normandy, who in 1793 becomes King Louis XVII, after his brother dies in 1789 and his father King Louis XVI is executed by guillotine.

Hugging the Queen’s side is her daughter Marie Thérèse Charlotte, given the title Madame Royale, and her only child to survive the Revolution. The Royal Crown is hidden in the top right corner of the painting, halfway outside of the composition, maybe in an attempt at conveying the Queen’s royal duties to be secondary to, and nearly forgotten in the light of, the duty and affection she has to her children.

This is in contrast to Marie Antoinette in Court Dress from nearly a decade earlier where the crown is more visually accessible. The cabinet on which the crown rests upon is a large jewelry box. About this box Heidi A. Strobel writes: “The inclusion of the large jewelry box behind the royal cradle was likely an allusion to the story of Cornelia, implying that the queen viewed her progeny, rather than her possessions, as her real wealth.”11 Cornelia was the daughter of Scipio Africanus, who defeated general Hannibal, and mother of the Gracchi brothers. Only one moment of her life is referenced in art: a Roman woman visits her and asks to see her jewels. In response, newly widowed but ever frugal and virtuous, Cornelia points to her two sons. This gesture proves her devotion to her family.12

Queen Marie Antoinette’s feet are slightly elevated on an ornate cushion, maybe in an attempt to give the illusion of resting her feet after a long day taking care of her children. She is wearing a simple and conservative red-orange dress, which she requested of her dressmaker Rose Bertin,13 decorated with white trimmings and a delicate lace. She adorns a matching hat, which is decorated with large white feathers and sits upon a white fabric partially covering her hair, and drapes down her neck and back.

This portrait of the Queen is a piece of propaganda, where Queen Marie Antoinette is depicted as inhabiting the bourgeoisie values of the affectionate and nurturing mother, rather than being the head of state and a political figure. The political instability of the time played a big role in the production of Vigée-LeBrun’s portraits of Marie Antoinette. As Louis XVI became king, he and his ministers saw that in order to keep social stability, there was a need for political reform.

The King had started to rely more and more on the bourgeoisie for political support, which angered the aristocracy who wanted to protect their privileges and keep the bourgeoisie from having a political voice.14 Therefore, the King wished to appeal to his bourgeoisie royalist subjects, who could support him in his wish for reform, through fine art. King Louis XVI put his trust in Count d’Angiviller, director of the Bâitments du Roi, ordering him to commission fine art that combined the idea of reform and related royal interests with those of the bourgeoisie, at least conceptually.

Vigée-LeBrun thus forwent details that marked her royal subject as a monarch – instead, she painted Marie Antoinette as a mother who understood her place in society was in the home, and that her highest duty was that of raising her children. This was a strategic attempt to better the bourgeoisie’s opinion of the Queen, which was worsening as the social unrest rose and state financial ruin loomed, by depicting her as familiar and exemplary.15

Such an image of motherhood conformed to the liberal Enlightenment (what one might label today as “conservative”) gender theory; philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau had in his novels Émile (1762) and The New Heloise (1761) emphasized that the duty of a mother was to nurture children and complete domestic tasks in the home. Rousseau wanted to separate the male and female social spheres, and identified female virtues as dependence, obedience, loyalty, and self-sacrifice.16 The Rococo and Neoclassical art movements of the time were influenced by the liberal Enlightenment ideas, which considered existing European institutions such as monarchy, Christianity, and the feudal system as part of a “divine plan”. Those on the liberal side of Enlightenment respected authority and tradition, and thus wanted change to happen gradually.17

The painting of the Queen and her children was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1788, the year before the revolution broke out, and known as “The Royal Family”.18 For the painting, Vigée-LeBrun prepared separate studies of le Dauphin, the Madame Royale, and the Duke of Normandy.19 In her Memoirs, after having sent the painting to the Salon of 1788, Vigée-LeBrun writes:

At last I sent my picture, but I could not muster up the courage to follow it and find out what its fate was to be, so afraid was I that it would be badly received by the public. In fact, I became quite ill with fright. I shut myself in my room, and there I was, praying to the Lord for the success of my "Royal Family," when my brother and a host of friends burst in to tell me that my picture had met with universal acclaim. After the Salon, the King, having had the picture transferred to Versailles, [...] vouchsafed to talk to me at some length and to tell me that he was very much pleased. Then he added, still looking at my work, "I know nothing about painting, but you make me like it.”20

The French government was impoverished after the Seven Years’ War (1756-63), from supporting the American Revolution (1775-83), and from the luxurious and royal lifestyle of the court. Since the aristocracy and the Roman Catholic Church were exempt from paying taxes, a lot of financial pressure was put on the commoners in order to pay the country’s debt from the 1770s and ‘80s. The King’s attempts at reform were being barred by the aristocracy and Church, and the commoners did not trust or like the government due to their financial exploitation of the already impoverished group. Frustrated by the political standstill, the unrest broke out in full in July of 1789, as the people stormed the Bastille. This was an important and pivotal moment in European history, as the King was challenged not by another royal rival, but by the people he was supposed to protect and uphold, who had begun to see themselves with as much political power as the King himself.21

David and Marat: the transformation of History Paintings

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) was a contemporary of Vigée-LeBrun, and a Master of History paintings. History paintings (not to be confused with historical paintings) were considered the highest of the hierarchy of art at the Académie Royale, and at the Paris Salon, where David studied and exhibited his paintings. History paintings use stories and themes from antiquity and Greco-Roman mythology, but David would later in his career change the content of these paintings from the past to the present.

David painted in a Neoclassical style, using somber colors, a simple composition, restrained brushwork, and an emphasis on lines. It developed as a reaction to the light and flirty Rococo that had come to represent the lavish aristocracy.22 Neoclassicism views antiquity as the model for a good society, both for behavior and the composition of social, political, and cultural reforms. This created a sort of “antiquomania” which affected stylistic trends, but later would also influence a deeper reflection on antiquity’s relationship with the modern world.23 To understand what makes David a pioneer of the new type of history painting, we must first look at his earlier works:

David’s The Oath of the Horatii from 1784 (figure 3) was a commission from Count d’Angiviller, who was continuing the strategy of his predecessor, the Marquis de Marigny, by trying to rejuvenate history painting as a vehicle for propaganda.24

The scene comes from Book I of Livy’s History of Rome from 26 BCE, where Livy tells of a dispute at the border of Rome and Alba: the city leaders agree to let a set of triplets from each side of the disagreement determine the outcome of the dispute, instead of starting a full on war; this is complicated by the fact that one of the Roman triplets, Horatius, was married to a sister of the Alban triplets, and one of the Romans’ sister, Camilla, was engaged to the Alban Curiatius – no matter the outcome, there could be no happy ever after. Only Horatius survives the battle, and, upon being scolded by Camilla for having killed her fiancé and who curses Rome in her grief, he kills his own sister in a fit of anger afraid for Rome’s future.25

David proposed to Count d’Angiviller to depict the last scene of the story, where the father of Horatius begs for the life of his son, who has been condemned to death. The father manages to save his son by convincing the judges of Horatius’ honorable service to Rome. David was a follower of the radical side of the Enlightenment, whose ideas reject institutional authority and values individual freedom, and thus he decided to depict another part of the story without asking for permission.26 He would, however, hide his republican sentiments in order to receive commissions from the monarchy.27

In the painting, we can see the father of the Roman triplets standing in the center. On the painting’s left, the triplets stand in a row with their arms outstretched and legs spread in a stance which reflects their psychological state. They are faced with the ultimate sacrifice for the state – their own lives – which they accept with honor and resolve. On the right we see the wives of Horatius and Curiatius in their passive, placid state quietly grieving over what is about to commence. A nanny stands behind them, clutching the women’s children.

In The Oath of the Horatii David combines Greuze’s so-called “moral paintings”, which conveys moral instructions through anonymous figures of contemporary commoners28, with his teacher Vien’s classicism. David references Greuze’s paintings by using a stage-like and simple setting, clear gestures and expressions, and dramatic lighting. These elements create a painting with a neoclassical visual, but contemporary moral message – an example of Roman virtue, intended to inspire its audience to submit to authority and sacrifice oneself in the interests of a higher cause.

As the painting was commissioned by Count d’Angiviller and belonged to his initiative for social and moral reform, the audience would have been expected to see the father as a symbol of King Louis XVI, the brothers as exemplifying ideal male behavior, and the women ideal female behavior. The painting was exhibited at the 1785 Salon, where it received an unlucky position due to being submitted late, which was done on purpose in order to heighten the public’s anticipation.29

The painting was exhibited again at the 1791 Salon, during the reign of the National Assembly government which passed a law minimizing the monarchy and limiting equality before the law. In light of this, The Oath of the Horatii then came to symbolize a people’s obedience to its central authority – a message as desirable for the new French form of government, just as it had been to the monarchy it wished to restrict.30 However, the painting could also be understood as a warning for what happens when one practices blind obedience to authority, as it might lead to tragedy.

In addition to painting another scene than originally approved by d’Angiviller, David also painted it in a much bigger format than agreed.31 Through this, the painting becomes a revolt and a demonstration of David’s artistic freedom. It is clear from David’s paintings, even while following the rules and preferences taught at the Académie Royale and being commissioned by the royalty, that he was a radical at heart – his art is as inseparable from politics as he was.

In 1793 David transformed the history painting genre into something new and innovative which would come to influence both his later works and those of his students. He painted one of his most famous works, The Death of Marat (figure 4), which depicts the tragic assassination of his friend and fellow revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat. Marat, nicknamed “the friend of the people” or “L’Ami du Peuple”, after his newspaper of the same name, was a widely read journalist and influential deputy at the National Convention.32 He was assassinated by a political opponent, Charlotte Corday, of which Nina R. Gelbart writes:

Corday became convinced that Marat was the principal instigator of the bloodshed in France, feeding the guillotine and fomenting civil war. Deciding to offer up her life for her patrie, she conceived the plan to stab him for all to see when he rose to speak at the National Convention, or at Bastille Day festivities on the Champ de Mars. With Marat silenced, she felt certain that peace would be restored to her beloved France.33

However, when she arrived in Paris she learnt that Marat had a skin condition, which often confined him to his home as he had to take soothing baths. She then devised a plan to kill him in his own home, and on the morning of the 13th of July, she went to his house by coach after buying a knife. She was turned away by the concierge and Simmone Évrard, Marat’s wife and fellow revolutionary, both claiming he was too ill to receive a visitor.34

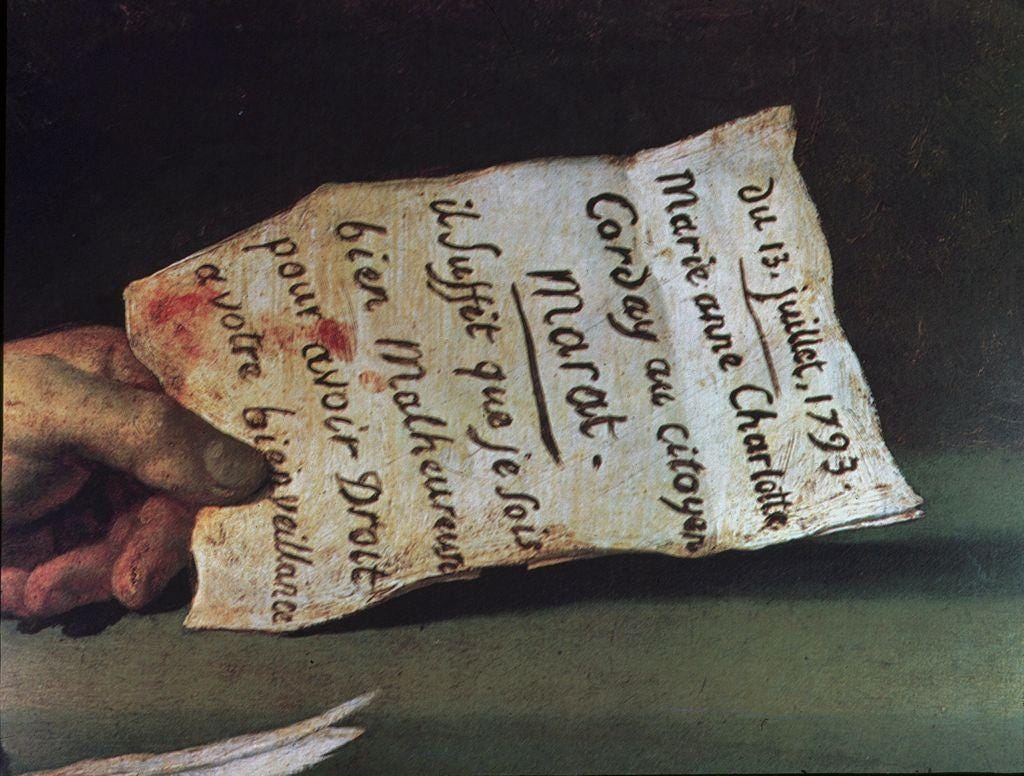

She then went to her lodgings, and, having seen letters arrive for Marat during her short visit at the gate, wrote a letter claiming that she had information on the fugitive Girondins, allegedly on march towards Paris in order to subvert the revolution, and that an interview with Marat would be crucial to his safety and the survival of the revolution. She was then later let into his home under this pretext, where she stabbed him in the bathtub.35

David painted the death of his friend in a Neoclassical style and the genre of history painting. The body of Marat lays lifeless in a bathtub draped in white and green fabric, some of which seems to lay over a hard surface on top of which Marat’s left arm also rests. In his left hand Marat holds the letter Corday sent, which reads “13th of July 1793. Marie-Anne Charlotte Corday to the citizen Marat. It’s sufficient enough that I am unhappy, to have the right to your benevolence.”36 This might have been something David put in himself, instead of being accurate to the letter Corday sent in which to gain access to Marat’s home.

The background is simple with a black to brown-green dotted gradient. This creates an emphasis on the main motif, which is Marat; the use of light and shadow creates an association to Caravaggio and chiaroscuro. The position of the body is similar to that of Jesus in Michelangelo’s Pietà and thus evokes an association to martyrdom. With this pose David is telling the viewer that Marat, like Jesus, died for what he believed in, and portrays his friend as a modern Christ or secular saint. This is further alluded to by the rendering of the fatal wound, which is beneath the right clavicle and looks similar to one of Jesus’ five holy wounds – a symbol of the nature of salvation itself.

One possible model for the pose might be an illustration of a marble relief in Edward Wright’s account of his journey to France and Italy in 1720-1722. David spent a total of six years in Rome and would there be devoting considerable time to drawing ancient sculptures. These studies would become an important source for his later works. The composition of the pose in David’s painting is cropped compared to the marble relief sculpture, which contains two figures, which Wright thought to be Venus and Adonis.37

Marat’s head rests gently on the bathtub’s edge, and his right arm hangs calmly over the edge. In his right hand is a quill, which seems to have quite recently been in use to write the papers on the wooden stand, a makeshift écritoire – a writing desk – next to the bathtub. Also on the écritoire is an assignat: a paper or fiat money which was used as banknotes during the French revolution – this is potentially the first visual depiction of an assignat in Western art.38 The low-value 5-livre assignat on Marat’s écritoire could be a charitable reply to Corday’s letter, and was also the first paper money experienced by the peasants, so-called sans-culotte (“without breeches”), of 1790s France.39 On the bottom half of the écritoire is written “To Marat” and a signature by David.

David continued to use his artistic skills to depict scenes of contemporary happenings with the grandeur and style of history paintings, something his students, such as Jean-August-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), would continue. In 1799 he became First Painter for the new Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, painting important moments in the emperor’s reign such as his coronation at the Notre-Dame de Paris in 1804. Élisabeth Vigée-LeBrun would continue painting portraits during her exile from France, and she wrote about her life in her memoirs.

Heidi A. Strobel, “Royal “Matronage” of Women Artists in the late-18th Century”, Woman’s Art Journal 26, no. 2, (2005): 3.

Michelle Facos. An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art. (Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2011), 11.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun: Woman Artist in Revolutionary France”.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 11.

Élisabeth Vigée-LeBrun, “Chapter II. Up The Ladder Of Fame” in The Memoirs of Madame Vigee LeBrun, trans. Lionel Strachey (New York: George Braziller Inc., 1903).

Simon Schama, “The Domestication of Majesty: Royal Family Portraiture, 1500-1850.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 17, no. 1 (1986): 177.

The Metropolitan Museum, “Marie Antoinette in Court Dress”.

Joseph Baillio, et al, “Catalogue” in Vigée Le Brun (New York: Yale University Press, 2016): 72.

Vigée-LeBrun, “Chapter II. Up The Ladder Of Fame”, trans. Lionel Strachey.

Atelier de Ricou, “Palace of Versailles – Salon de la Paix”.

Strobel, “Royal “Matronage” of Women Artists in the late-18th Century”, 6.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 49.

Strobel, “Royal “Matronage” of Women Artists in the late-18th Century”, 6.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 37.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 12.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 12.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 6.

Vigée-LeBrun, “Chapter II. Up The Ladder Of Fame”, trans. Lionel Strachey.

Vigée-LeBrun, “Chapter II. Up The Ladder Of Fame”, trans. Lionel Strachey.

Vigée-LeBrun, “Chapter II. Up The Ladder Of Fame”, trans. Lionel Strachey.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 38.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 28.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 27.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 38.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 39.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 39.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 56.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 9.

Thomas Crow, Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth Century Paris. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985): 214.

Facos, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art, 40.

Crow, Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth Century Paris, 214.

Nina Rattner Gelbart, “The Blonding of Charlotte Corday”, Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no.1 (2004): 202.

Gelbart, “The Blonding of Charlotte Corday”, 202.

Gelbart, “The Blonding of Charlotte Corday”, 202.

Gelbart, “The Blonding of Charlotte Corday”, 202.

David, close up of Death of Marat, 1793. My translation.

Hanno-Walter Kruft. “An Antique Model for David’s ‘Death of Marat.’” The Burlington Magazine 125, no. 967 (1983): 606.

Spieth, Darius A. “THE CORSETS ASSIGNAT IN DAVID’S ‘DEATH OF MARAT.’” Source: Notes in the History of Art 25, no. 3 (2006): 22.

Spieth, Darius A. “THE CORSETS ASSIGNAT IN DAVID’S ‘DEATH OF MARAT.’” Source: Notes in the History of Art 25, no. 3 (2006): 22.