Hi everyone! Sorry for the late review for Carmilla, to hopefully make up for it I have decided to combine it with my review of Giovanni’s Room. Spoilers ahead, if that needs to be said. Let’s get into it!

Carmilla

I didn’t quite know what to expect from this short novel of lesbian vampire romance. I found myself entranced in the beautiful, gothic, dark landscape which Sheridan Le Fanu so vividly paints a picture of. I thought it very interesting that it written as if Laura is telling—or confessing?—what happened many years after the events of the novel. I was intrigued by the story, but it felt at the same time a little predictable; how it was revealed later that Carmilla had been preying upon another young woman like Laura not long before she came to stay at Laura’s castle, was probably some of the more interesting aspects to me. Maybe it’s because we are so used to vampire fiction today that I felt I knew the story just by knowing the very fact that Carmilla is a vampire.

It is interesting, however, how Carmilla acted. I found that she was not afraid to say what the others wanted to hear; when Laura started having nightmares and getting sick, Carmilla relayed a similar story—it made me think she wanted to convince her hosts that she, too, was a victim, when in reality she was the plague that had struck them all along. How they found her locking her bedroom door during the night, or refusing to sleep with servants nearby, not suspicious I will not know—especially after that night where she most certainly was not in her room.

I was a little surprised at how fast Carmilla’s love for Laura seemed to develop. (And what did Laura feel for her back? That’s something I’m not sure I got the answer to.) Though they did spend many weeks together, all of sudden Carmilla declares her love—and quite intensely, too, with talking about life and death. Yet, I continuously (especially during the later parts) found myself annotating “gay”, “more gay”, “very lesbian” and the like in the margins.

It is no secret that vampirism in the Victorian era is a euphemism or stand in for, among other tings, sexuality—especially homosexuality. We see this in Stoker’s Dracula, too, which actually postdates Carmilla by nearly 25 years. The fear of the unknown, the fear of the perverse, the fear of the monster—these are the core themes in gothic fiction, especially in Victorian times (who were in some sense scared of everything).

Foucault writes in his History of Sexuality, that contrary to popular belief the Victorians were not so prudish that all talk of sexuality ceased to be; instead, discourse about sexuality exploded! They talked about it in church, at school, in the hospital, at home—they created laws and regulations, categories of perversion, categories of sexual orientation. True, the goal was often to suppress sexuality making an appearance in public—it was to be a private, adult, hidden thing—yet in their literature, art, and culture sexuality was everywhere. One way to talk about it was through monsters, especially vampires—what is not sexy about someone kissing your sensitive neck (often hidden under clothes), and killing you slowly at the same time?

All in all, the novel was very well written and held my attention. But, vampires having existed in our fiction for so long now, I was not surprised at any turn of the story. I felt I knew how it would end before I even read the first sentence, which is not necessarily a bad thing, but definitely less surprising than it might have been to a Victorian reader. It was sufficiently homoerotic, homoromantic even, and of course—with a tragic end.

Giovanni’s Room

Talking of tragedy, Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin is filled with it to the brim. David is wrought with internalized homophobia, Giovanni is wrecked by heartbreak, Hella’s dream of being a woman is taken from her, Guillaume murdered; it ends well for no one, not even Jacques comes out of it unscathed.

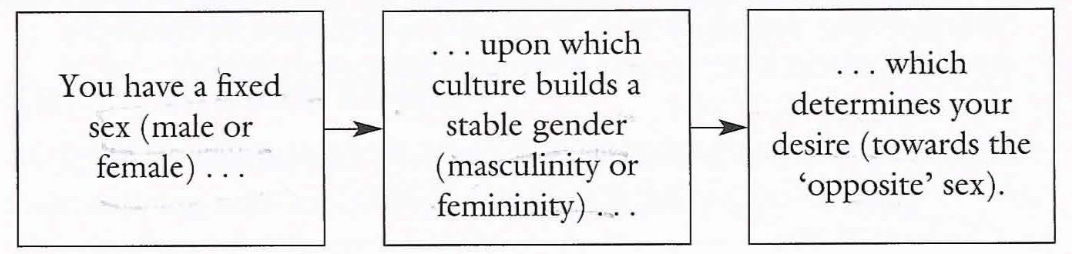

While reading this novel I kept thinking of why David was so at odds with his sexuality, and it lead me to thinking of masculinity. Philosopher and scholar Judith Butler, famous for her book Gender Trouble, uses the term “heterosexual matrix” to describe how society expects one to be heterosexual on the basis of their sex (gender), as well as uses this matrix to naturalize heterosexuality. Here is a visualization of the matrix, as drawn up by David Gauntlett1:

Notice the arrows, how one aspect leads to the other; it is expected—normalized—that one should identify with the sex one is born with, and hence feel attraction to the opposite sex. But we know that this is not always true.

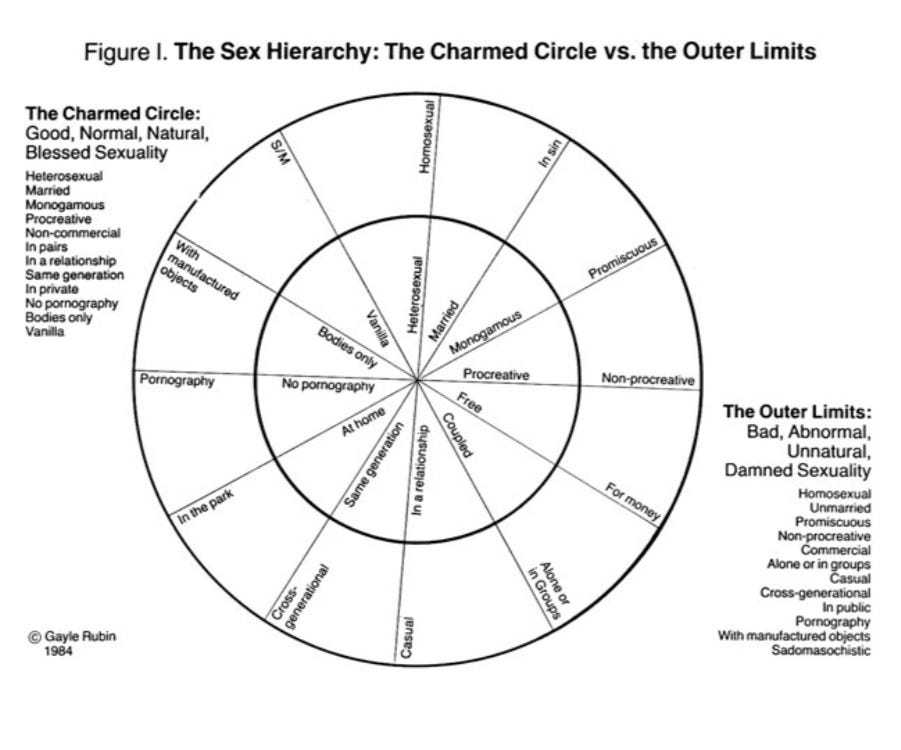

Similar to this, Gayle Rubin’s “The Charmed Circle” from her book Deviations2 illustrates the acceptable, “normal”, good sexuality (inner circle), and how it differs and is in opposition to unacceptable, “abnormal”, bad sexuality (outer circle/limits).

The inner circle is heterosexual, monogamous, married, procreative, private and so on. On the other hand, the outer limits of sexuality are homosexual, polyamorous, non-married or promiscuous, non-procreative, public, and so on. Combining, then, the heterosexual matrix and the charmed circle, we can conclude that not only are we expected by society to be heterosexual, but we are also expected to practice (or perhaps inhabit) a “normal” heterosexuality—one that falls within the inner circle, and dares not consider stepping, even for a moment, out of the bounds.

R. W. Connell writes in his book Masculinities of the “Social Organization of Masculinity”, and states that there are four types of masculinities—should one find a way to define what being masculine means—which are as follows3:

Hegemony

Subordination

Complicity

Marginalization

(I will only discuss the top two in this review, so if you are interested in the rest, I suggest you read Connell’s chapter. It is relatively short.)

Simply put, the hegemonic masculinity is the ideal, the currently accepted masculinity which rules over the others—in our Western society that would be white, heterosexual, with some sort of strong or “masculine” appearance (think of male celebrities, politicians, businessmen, etc.). This masculinity can be said to be a byproduct of the patriarchy, where men are dominant and women submissive. This masculinity is the embodiment of power, in a sense. It has a cultural dominance over society as a whole, including and not limited to other groups of men.

Below this hegemonic masculinity is subordination. It is in this category we often find (white) gay men—men who do not fit into the hegemonic masculinity, who are subordinate to it, and who are excluded culturally and politically, discriminated on the streets and in legal systems, who might struggle economically or otherwise due to his “abnormal” sexuality. This is where all the gay characters in Giovanni’s Room fit in; what David so desperately tries to escape. He wants more than anything to be part of the hegemonic masculinity, and thus rejects his social placement in the subordinate one, going so far as to reject within himself his own sexuality which he feels betrays him.

In one passage, he says:

Yet it was true, I recalled, […] I wanted children. I wanted to be inside again, with the light and safety, with my manhood unquestioned, watching my woman put my children to bed. […] It had been so once; it had almost been so once. I would make it so again. I could make it real. It only demanded a short, hard strength for me to become myself again.

When I read this I felt immediately that David was lying to himself, trying to compromise for something. He hates his sexuality by which society deems him abnormal, outcast, perverse. He wants to lead a so-called normal life, one where he is a father and a husband—a hegemonic masculinity, one following the heterosexual matrix and the inner rings of the charmed circle—who does not have his manhood questioned.

He thinks that to realize this dream it would “only [require] a short, hard strength”, as if he could in one fell swoop push aside any and all of his homosexual desires, once and for all establishing himself in the hegemonic masculinity he so wishes to be a part of—that he seems to think he was once a part of, as if Paris had somehow corrupted him to become gay.

Later David says, in a fight with Giovanni:

[Giovanni] was pale. “You are the one who keeps talking about what I want. But I have only been talking about who I want.”

“But I’m a man,” I cried, “a man! What do you think can happen between us?”

“You know very well,” said Giovanni, slowly, “what can happen between us. It is for that reason you are leaving me.”

Giovanni is right: David knows very well what can happen—emotionally, physically—between two men. That is precisely what he is afraid of to admit, to commit. His love for Giovanni, a love which David despises yet cannot help but feel, is exactly why he is leaving him.

To sum up, this is why I think David struggles so immensely with his sexuality; he shuns himself for having a sexuality, against his wishes, that is deemed “abnormal”—even in Paris, which one might think of as the city of love, he is appalled by himself and others like him. He mentions several times how he feels at once both desire and disgust when he is with Giovanni.

David describes the gay men he sees in bars as “fairies”, “les folles” (the queens), and “tapettes”, all derogatory names for effeminate gay men4. It is clear that he has some sort of contempt for them—some sort of “us” vs “them” thinking. He does not identify with their way of expressing their sexuality, he does not want to identify with it. He is aware that their masculinity is explicitly subordinate to his ideal one, his fake one; he wishes, more than anything, to fit in with the hegemonic masculinity. And to achieve this—though his success could be up for debate—he breaks his own heart, as well as both Giovanni’s and Hella’s.

I think part of the tragedy of this beautiful novel is not that Giovanni is sentenced to death, nor that two men who love each other cannot be together—rather the tragedy is that David refuses to be with Giovanni, because he cannot come to terms with the fact that he is attracted to men. He does not want to be attracted to men. At some point he goes to bed with a female friend precisely because he cannot stand the fact that he likes men.

That is the tragedy: David, by refusing to accept himself, by trying so desperately to escape what his heart wants, to escape himself, sentences Giovanni to death, and himself to solitary madness. All because he could not accept that he loved a man.

David Gauntlett, “Queer Theory and Fluid identity” in Media, Gender and Identity: an Introduction (London: Routledge, 2008). P. 148.

Gayle Rubin, Deviations: A Gayle Rubin Reader (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011). P. 152.

R. W. Connell, “The Social Organization of Masculinity” in Masculinities (Cambridge: Polity press, 1995). P. 76-81

If you want to read more on this topic, Alexis Annes and Meredith Redlin’s paper “The Careful Balance of Gender and Sexuality: Rural Gay Men, The Heterosexual Matrix, and “Effeminophobia””in Journal of Homosexuality, 59(2), 2012, p. 256 - 288 is worth a read.

Giovanni's Room. "I wanted children. I wanted to be inside again...watching my woman put my children to bed." When I read this I thought, at least for now, he could have children and watch his man/husband put their children to bed. Today, David might still refuse to be be with Giovanni and not want to be attracted to men. But, it would be a different struggle.

I also have to say, Baldwin writes exquisitely. Every page. Every word.

His way of showing change is amazing. He uses the seasons in two paragraphs but it is so much more than seasonal change.

Winter turns to Spring. Part 2 beginning of chapter 1 the paragraph that begins "Every morning the sky and the sun seemed to be a little higher...

Autumn turns to Winter. Part 2 end of chapter 4 the paragraph begins "The days that followed seemed to fly..."

Carmilla. I too loved the beautiful, gothic,dark landscape. As you say, vampires have existed in our fiction for so long there are few surprises. But what if Carmilla, not Dracula, was our vampire archetype? Copied. Taught in school. Movies. With 150 years of female vampires as the standard, what would the genre look like?