Is art inherent to human nature?

An Essay On: What studying art history actually makes me think about.

For a while now, even before starting my BA in Art History last fall, I’ve had a thought gnawing at the back of my mind: is art an inherent part of human nature? And furthermore, what inspires one to make art? Are humans the only ones who are capable of making art?

These are the questions I would like to explore in this essay.

These are quite up-in-the-air and might seem hard to find an answer to, or at least a concrete one. There can be many reasons for one to make art, to be an artist, to admire art, to love art. An appreciation of beauty, of the world, of what one is surrounded by - of one’s life.

Maybe one has always been fond of color and light, and through these visual tools wants to etch into stone - or canvas - a moment in time. Maybe one wants to record something important to them, or reminisce about a memory, or imagine something entirely new.

Try as I might, the answer I always come to seems to be… humanity.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Let’s look at Merriam-Webster’s definition of the noun “Art”, slightly abbreviated by me1:

1: skill acquired by experience, study, or observation

- the art of making friends

[…]

4:

a) the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects

-the art of painting landscapes

also : works so produced

- a gallery for modern art

For our purpose today number 4 is probably the best suited, because - being the Art History nerd I am - I’m interested in the visual (and sometimes physical) manifestation of human creativity and skill.

There’s no hiding that there have been many great artists throughout the history of mankind, and they all have something in common: the conscious use of skill and creative imagination, exactly as Merriam-Webster defines it.

From cave paintings and petroglyphs to contemporary artworks, the artists behind them all used their skills and creativity to depict their chosen scenes in a particular way - perhaps produced by the limitations, or freedom, of their tools and time.

But where do we learn such skills? Where do we, as human beings, learn to harness that creativity and apply it to the production of visual and aesthetic objects?

For a while I’ve wondered if it is something we’re born with, a talent of sorts that’s ingrained deep into our very DNA. Though some may say that talent is something reserved for only the Special Someones, I would disagree. While I do think one can inhabit a certain knack for a skill such as creating art (or any other skill humans can do) I don’t believe that one has to “be born with talent” to be able to create art. As Merriam-Webster says, another definition of “Art” is:

“skill acquired by experience, study, or observation”.

This is not only true for things such as “the art of cooking” or “the art of making friends”, but also for learning to create art. Art is a skill, and a demanding one - no matter how much ‘talent’ one is born with. One of the most important things to create visual depictions, no matter how photorealistic or stylized it is, is to observe it first.

There is, of course, a reason that the old art academies in France, England and elsewhere put such an emphasis on studying anatomy, making still lifes and figure drawings, practicing values and the most basic of shapes. If you’ve ever tried to draw something from your imagination, even though you believe you know exactly what it looks like, it usually ends up looking …less than realistic. But at the same time, humans are great at pattern recognition! Which is what allows us to recognize that drawing, even if it’s just a smiley-face.

Pattern recognition is, simply put, matching information received with information that is already stored in the brain; using information we already know to recognize and categorize something new. The human brain is very good at pattern recognition, and you might have heard somewhere it’s the reason we as a species has such a good survivability rate - being able to recognize potential foes and friends is an important ability in survival. From recognizing poisonous berries to recognizing the structure of a human (or non-human) face, there’s a lot of uses where pattern recognition can come in handy.

It’s this pattern recognition that can deconstruct the human face down to the simplest forms - eyes, nose, mouth - and piece that information back together to see a circle with two dots and a curved line as a smiling human face. (I could add something here about how we create art in ‘our image’ like God made us in '‘His’, but I’m not particularly religious and that’s also a bigger discussion for another time).

If you’ve ever dabbled in visual arts, or gone to elementary school Arts & Crafts class, you might’ve come across a little something called “color theory”. Color theory can seem at once both easy to grasp (red and blue make purple, orange and blue are opposites) and quite difficult at times (hue, value, saturation/chroma, additive VS subtractive, cohesive color palette etc.).

You might have seen some videos on social media where the artist, usually on a digital art program, picks a color from one side of the screen and drags it across to the other side where it looks completely different, and says “Color theory?!?!?!?”. I certainly have seen my share of those, and even though I know some basics of why this seemingly color-changing phenomenon happens, I still feel fascinated by how our brain perceives colors when they’re in a certain environment.

Which leads me to the question: if there is an inherent ability to create art in the human condition, why is it so that there are still parts of art theory and art making that is something that has to be learned? Why am I not born with the inherent ability to understand color theory and all its nuisances perfectly, if I am born with the ability to - out of mere nothingness - create a visual picture? Where is the inherent ability to understand art? Should not my understanding of art be absolute?

Is there a cap or a maximum to the knowledge a human is born with? German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900-2002) wrote about hermeneutics, a branch of knowledge that deals with interpretation (usually of the Bible or other religious texts, but also the art of understanding and communication). Gadamer builds on his teacher, Martin Heidegger’s, theories, which the latter wrote in the philosophical book Being and Time from 1927. Gadamer’s book Truth and Method (1960), in which he expands on Heidegger’s theories of “philosophical hermeneutics” is considered his magnum opus.

To Gadamer, hermeneutics is more fundamental than just a scientific method. He believes that hermeneutics claims universality (meaning existing everywhere or involving everyone). He thinks that hermeneutics will show what happens when we understand something - what prerequisites are fundamental for understanding.

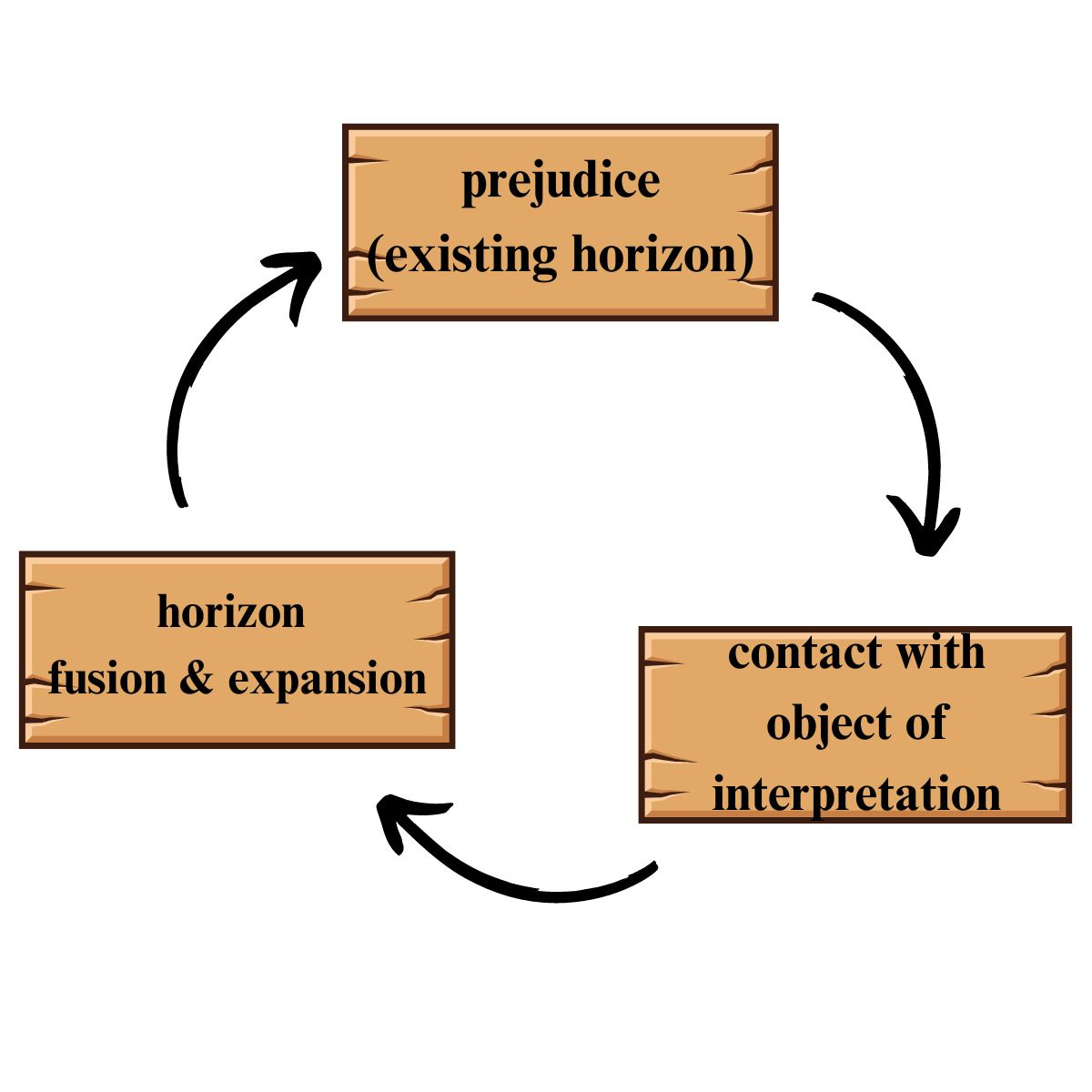

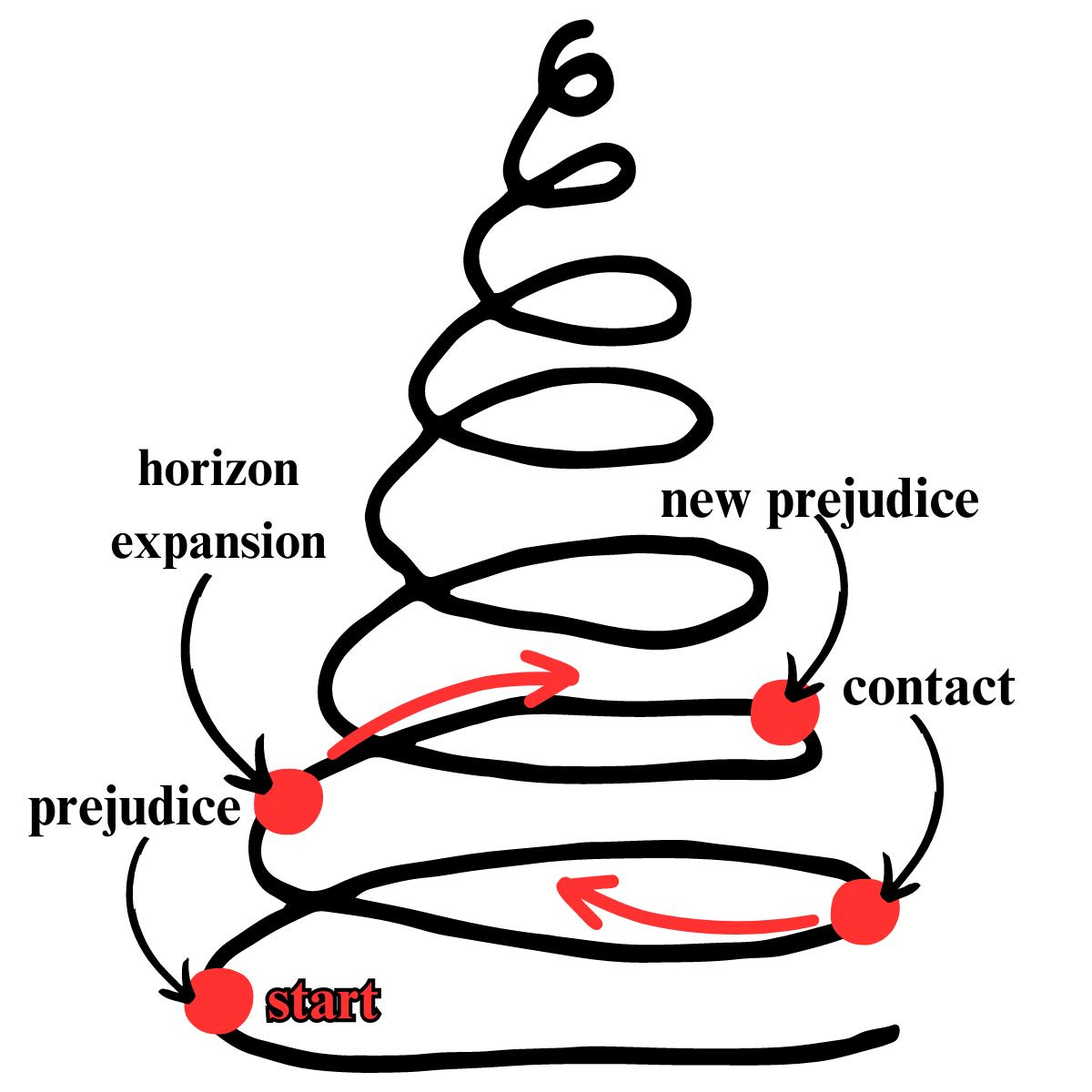

His main point is that “all understanding is permeated by prejudices”.2 We can think of this as a sort of spiral of knowledge that builds on itself, possessing a circularity: all understanding builds on something that is already understood - understanding is only possible under the prerequisite that something is already understood.

The knowledge we already possess, and that information we receive is categorized through, is called the “horizon of understanding”. One is not aware of the totality of one’s own horizon. The object of interpretation also has its own horizon, and the goal of understanding is the fusion of these horizons. In other words, understanding is the constant expanding of one’s horizon.

Okay, this is turning into a little bit of a word salad, so let me give you a simple example:

The human face can be, at the most fundamental level, broken down into two simple, geometrical shapes: a curved line, and two dots/filled ovals.

If you put these in a certain position relevant to each other, we get something the human brain can recognize as a face - a smiley-face! (Or a sad one, if you wish…)

This works because the brain uses its pattern recognition to create a prejudice (foundation for understanding; the horizon of understanding) of what the human face looks like. Upon recognizing the smiley-face as mirroring the human image, the viewer’s horizon is expanded as it fuses with the object’s, and the two come to a mutual understanding (pun intended).

So what does this teach us about whether art is inherent or not? Perhaps not as much as I’d like, at least in this simplified, almost superficial run-through of hermeneutics. But I thought it could be a nice reflection on how we learn and come to understand the world around us. So moral of the story: to understand something, we need to have a foundation of knowledge to analyze and categorize it through.

Armed with this knowledge, we can ask the question again: is art inherent to human nature?

When I envision what is needed to possess the ability to create art, what do I imagine? Where does the creation of art live in my horizon of understanding? For me, the creation of art in an expression of the human condition; a way for us to catalogue the world and simultaneously share it with those around us. To do this one will need a couple of things:

a brain to absorb information gathered by the body’s five senses,

a consciousness able to interpret, dissect and assemble that information,

and a surface or material on or with which to express that interpretation.

With these three conditions met, one can make art! In fact, humans have been making art since paleolithic times, by visually depicting the world around them (often animals and human figures) on the walls of the caves in which they lived, by smearing paint made from natural pigments with their fingers (or other tools).3

So it’s …easy to make art? Well, I guess! Or maybe it’s the fact that the human body comes out of the womb already equipped with two out of my three conditions. The only thing missing is the materials and extra (/optional) tools with which to create the art, such as paint, graphite, marble, wood, textiles, or whatever else your heart desires.

Is it then the fact that we are born with 66% of the conditions met, which enables us to make art? Chimpanzees are humans’ closest living relatives, possessing at least one of the conditions: a brain in a body with five senses - perhaps a consciousness, too, if I’m being relatively generous. If we gave them material with which to create art, would they? Or, rather, why do they not develop tools and material from the world around them like we do?

Maybe, then, there must be something in human nature which allows us - and us alone - to create art. If our closest living relatives are not creating art despite being quite similar us, does that mean humans have evolved to possess something truly unique which allows for creativity and the expression of that creativity?

So maybe art is not only inherent to human nature, but also unique.

—

Thank you so much for reading my essay; I hope it wasn’t too all over the place. Please share any thoughts you have in the comments down below! I’d love to hear your take on this topic. If you liked this and would like more similar essays in your inbox, please consider subscribing to my newsletter! Or you can share it with friends and family - it would really mean a lot to me.

I’ll leave you guys with a quote from a YouTuber I like quite a lot, but I couldn’t manage to fit into the essay (I wrote it in a rather flow-of-consciousness style):

“Hobbies are inherently enjoyable even if they are inefficient. No, rather isn’t it fun because it’s inefficient? […] Humans cannot live on efficiency alone.”

- MINJYE 4

Merriam-Webster, “Art” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/art accessed 11 may 2024.

From my textbook from my Intro To Philosophy course; no english version is available, and I no longer have access to the book itself, only my notes.

McDermott, Amy. “What was the first “art”? How would we know?” https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2117561118 accessed 11 may 2024.

MINJYE, “[💗1 hour] 🤚 With the left hand cam... Draw 3 full-body characters 2🥰 [Draw with me/Clip Studio]” Timestamp 34:50. Accessed 11 may 2024.

Kode- This is very true: “Pattern recognition is, simply put, matching information received with information that is already stored in the brain; using information we already know to recognize and categorize something new.” And what a great question on whether art is an inherent part of human nature. I’m leaning towards yes.